On his website George Monbiot writes that:

While you can be definitively wrong, you cannot be definitely right. The best anyone can do is constantly to review the evidence and to keep improving and updating their knowledge. Journalism which attempts this is worth reading. Journalism which does not is a waste of time.

Just as importantly, journalists should show how they reach their conclusions, by providing sources for the facts they cite. Trust no one, but trust least those who cannot provide references. A charlatan, in any field, is someone who will not show you his records.

This is good to know, in the light of an article he wrote called:

In an age of robots, schools are teaching our children to be redundant

As a trainee Luddite I was quite hopeful when I saw this title, maybe it would be an attack on the mechanisation of our schools from the enthusiastic techno-warriors who try to ruin the environment of education by throwing technology at every child as soon as they have learnt to gurgle and cry. But no.

The piece opens with this paragraph:

In the future, if you want a job, you must be as unlike a machine as possible: creative, critical and socially skilled. So why are children being taught to behave like machines?

As Monbiot suggests, he cannot be definitely right when he writes this. Yet has he reviewed the evidence? Has he updated his knowledge? Has he provided evidence for the facts he has cited? Has he shown us his records?

Well, maybe he has a crystal ball, but I’m not sure he knows what the jobs of the future will be like. Although I’m surprised that he implies education is primarily for preparing children for jobs I wonder what jobs he is thinking of, I’d like to see his evidence for this assertion. Finally, evidence wise, which schools are teaching children to behave like machines? I only ask because Monbiot suggests I should:

Trust no one, but trust least those who cannot provide references…

Monbiot writes that:

…why is collaboration in tests and exams called cheating?

He doesn’t provide sources for the facts he is citing here, but as a drama teacher I can assure him that at A level and GCSE collaboration is not called cheating…

but, of course, it might be him referring to written exams only… but this misunderstands group work, sometimes children try to hide they can’t read or can’t do a task, assessment is important for the teacher to find out who can’t do something so that they might help the pupil. If every test was collaborative, would the education for the future that Monbiot has already described achieve his aim? But, oddly, Monbiot believes the schools we currently have are:

…designed to produce the workforce required by 19th-century factories. The desired product was workers who would sit silently at their benches all day, behaving identically, to produce identical products, submitting to punishment if they failed to achieve the requisite standards. Collaboration and critical thinking were just what the factory owners wished to discourage.

Yet if we do a bit of research we can see that in the 19th century, the schools which were designed to:

provide for England’s newly-industrialised and (partly) enfranchised society

Were not ones in which

workers who would sit silently at their benches all day

In ‘Schools of Industry’ (As factory school as you can get):

The children were taught reading and writing, geography and religion. Thirty of the older girls were employed in knitting, sewing, spinning and housework, and 36 younger girls were employed in knitting only. The older boys were taught shoemaking, and the younger boys prepared machinery for carding wool. The older girls assisted in preparing breakfast, which was provided in the school at a small weekly charge. They were also taught laundry work. The staff consisted of one schoolmaster, two teachers of spinning and knitting, and one teacher for shoemaking. (Hadow 1926:3-4) In 1846 the Committee of Council on Education began making grants to day schools of industry towards the provision of gardens, trade workshops, kitchens and wash-houses, and for gratuities to the masters who taught boys gardening and crafts and to the mistresses who gave ‘satisfactory instruction in domestic economy’ (Hadow 1926:9).

Sounds like collaboration was needed, and not too much sitting in rows.

This is similar to Monitorial Schools:

The curriculum… was… the ‘three Rs’ (reading, writing and ‘rithmetic) plus practical activities such as cobbling, tailoring, gardening, simple agricultural operations for boys, and spinning, sewing, knitting, lace-making and baking for girls.

Whereas in Infant Schools:

The first infant school was established by Robert Owen (1771-1858) in New Lanark, Scotland, in 1816. Children were admitted at the age of two and cared for while their parents were at work in the local cotton mills. The instruction of children under six was to consist of ‘whatever might be supposed useful that they could understand, and much attention was devoted to singing, dancing, and playing’ (Hadow 1931:3).

Elementary Schools:

The question of how to organise children above the age of six in elementary schools was first addressed in Great Britain by David Stow (1793-1864)… He believed that in primary education the living voice was more important than the printed page, so he laid great stress on oral class teaching.

All this information is freely available here. It gives a lie to Monbiot’s assertion about what the 19th century education was like.

Monbiot’s assertion also ignores the social pioneers who pressed for reform throughout the 19th century, resulting in more schools educating the poor, educating girls, and also providing education education for ‘special needs’ children.

As for other schools, for the more ‘well-to-do’ the 1868 Taunton Report recommended, along class lines that schools should be seen as three different types:

first-grade schools with a leaving age of 18 or 19 would provide a ‘liberal education’ – including Latin and Greek – to prepare upper and upper-middle class boys for the universities and the older professions;

second-grade schools with a leaving age of 16 or 17 would teach two modern languages besides Latin to prepare middle class boys for the army, the newer professions and departments of the Civil Service; and

third-grade schools with a leaving age of 14 or 15 would teach the elements of French and Latin to lower middle class boys, who would be expected to become ‘small tenant farmers, small tradesmen, and superior artisans’. (The Commissioners treated these schools as secondary schools because the Elementary School Code of 1860 had fixed the leaving age for elementary schools at 12).

The Elementary Schools act of 1870 which took up to 20 years to enact is one where schools:

catered for children up to 14;

were for the working class;

provided a restricted curriculum with the emphasis almost exclusively on the ‘3Rs’ (reading, writing and ‘rithmetic);

pursued other, less clearly defined, aims including social-disciplinary objectives (acceptance of the teacher’s authority, the need for punctuality, obedience, conformity etc);

operated the ‘monitorial’ system, whereby a teacher supervised a large class with assistance from a team of monitors (usually older pupils).

Perhaps these are the schools Monbiot meant? Some of which were only around for the last decade of the 19th century. These schools were not preparing children for the 19th century factory but, maybe, the 20th century one. Yet they were also doing something socially extraordinary, if we look back to 19th century Sunday Schools in which no child was taught:

writing or arithmetic or any of the ‘more dangerous subjects’

because they were:

‘less necessary or even harmful’

The fact that poorer children were being taught to read and write and do their sums was a great advance. Yet even then, at the end of the century, further social reformers were looking to improve the academic level of education for the poor, which led to many great schooling innovations in the twentieth century.

I have a great deal of sympathy with many of Monbiot’s sentiments, but his inability to provide much evidence at all for his assertions in the first half of his piece then leads to worries about the singular nature of the evidence he provides in the second half of his article.

In fact the whole piece reads as though instead of

constantly reviewing the evidence and keep improving and updating his knowledge

it looks as though he already had a conclusion in mind and went on social media to provide ammunition for his prejudices.

Surely he wouldn’t have done something like that?

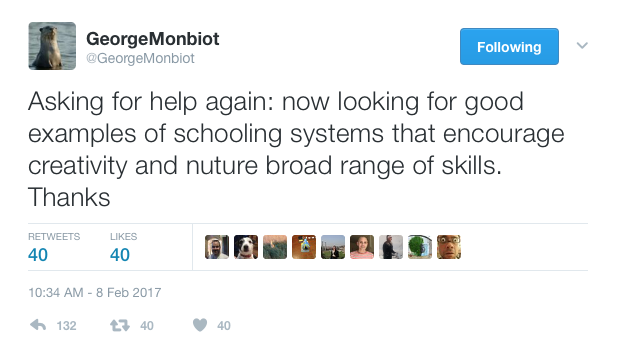

And yet on the 8th February Monbiot had tweeted this:

Next time, wouldn’t it be interesting if Monbiot followed his own advice and tried to produce (I paraphrase):

Journalism that is worth reading.

NB The image above is from the USA somewhere between 1900 and 1920

Leave a comment